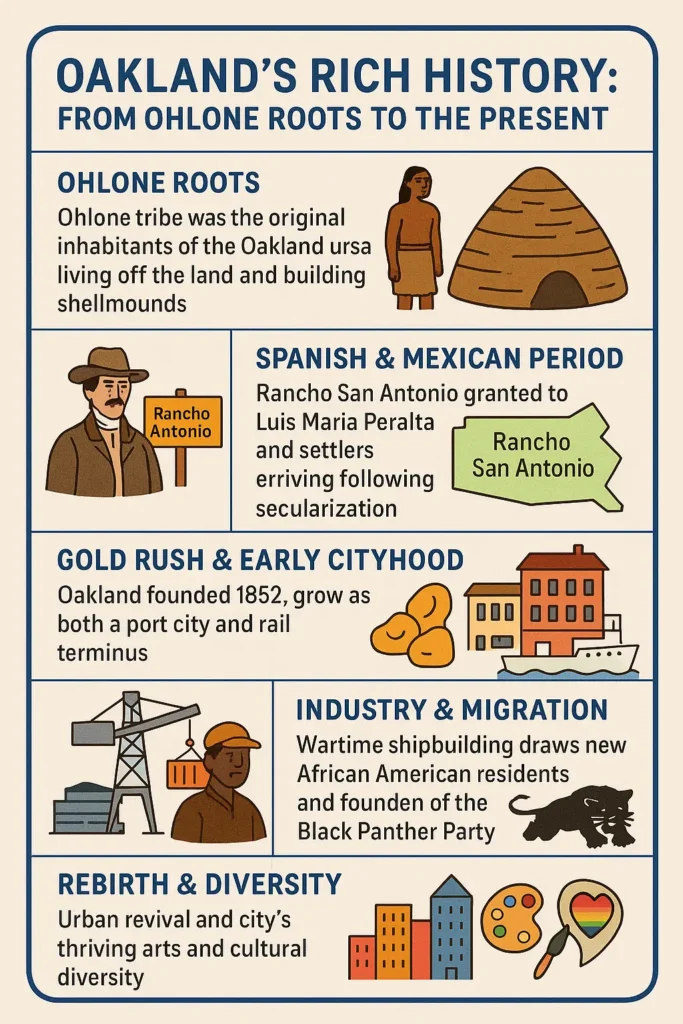

Oakland’s story stretches back far beyond its modern skyline. The Oakland area was home to the Ohlone (also called Costanoan) Native American tribes for thousands of years. The Ohlone (Costanoan) people were the original inhabitants of the Oakland area, living off the land and building shellmounds for ceremonial and burial purposes. For millennia these indigenous communities thrived in the East Bay, hunting deer and rabbits in oak woodlands and gathering acorns and shellfish from the bay. They built large shellmounds – massive heaps of shells and earth that served as burial monuments. Over 400 of these sacred mounds once dotted the Bay Area shoreline, but virtually none survive today. Today, Oakland’s place names and cultural memory (and even a park and college) preserve the Ohlone heritage, reminding us that the city’s history began long before Europeans arrived.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Spanish and then Mexican control reshaped the region. Spanish explorers came through California in the late 18th century, and by 1797 Mission San José was founded in nearby Fremont to bring the Ohlone people into the colonial mission system. This mission era disrupted traditional life. Around 1820 the Spanish crown granted a huge 44,800-acre rancho called San Antonio to soldier Luis María Peralta, which covered what would become Oakland and much of Alameda County. When Mexico became independent (1821) it secularized mission lands but confirmed the Peralta grant. After Luis Peralta died in 1842, his ranch lands were divided among his sons. Two sons (Antonio María and Vicente) inherited the portion that is now Oakland and began selling lots to incoming settlers. American ranchers and loggers moved in, cutting down the oak-covered hills and farming the land. (By the 1840s full-scale logging was underway in the East Bay hills.)

By the Gold Rush, a new city was forming. In 1851 Horace Carpentier built a trans-bay ferry to San Francisco, and in 1852 he and partners laid out the town west of Brooklyn and named it Oakland for the abundant oak trees on the grassy plain. The California legislature officially incorporated the Town of Oakland in May 1852. Downtown street grids were planned, lots were sold, and Oakland quickly outgrew its neighbors. A bridge was even built in 1853 to link Oakland with the town of Brooklyn across a slough, and by 1872 the two were consolidated into the city of Oakland.

With cityhood came booming transportation. In 1869 Oakland won a major prize: it was chosen as the western terminus of the first Transcontinental Railroad. Suddenly, thousands of people and tons of cargo poured through the waterfront. Wooden docks and warehouses sprang up along the estuary. Even today the site of Oakland’s railroad pier and the iconic white ship cranes (seen above) remind us of that era. (Indeed, Oakland’s deep natural harbor made it the obvious choice for a rail terminus.) The city’s importance grew again after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when displaced residents moved across the bay to Oakland, swelling its population overnight.

Oakland in the 20th Century: Industry and Migration

Oakland’s economy grew with the times. Industries clustered around the port and rail lines. In World War II, Oakland became a center of war production. Shipyards like Moore Dry Dock and the great Kaiser shipyards on the waterfront employed tens of thousands. This in turn drew a massive influx of workers from outside California. Many African Americans migrated from the Jim Crow South for these jobs. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Oakland’s Black population jumped from about 8,500 (roughly 3%) in 1940 to nearly 50,000 by 1950, illustrating the dramatic wartime boom. New housing and neighborhoods appeared in West Oakland and other areas to accommodate the growing labor force (even as segregation and discriminatory policies often limited where people could live).

After World War II, the city both prospered and faced challenges. The Bay Bridge (opened 1936) and later the BART subway (opened 1972) linked Oakland more closely to the Bay Area. By the 1950s Oakland’s population hit a peak around 385,000. But prosperity faded in some areas: deindustrialization and suburban flight led to urban decline. In the 1960s and 70s Oakland struggled with poverty and unrest. In 1966, Oakland saw the founding of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, a revolutionary group organized by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to fight police brutality. The Panthers became a defining part of Oakland’s identity during the Civil Rights era. Local leadership also began to change; in 1977 Lionel Wilson became the city’s first African-American mayor, reflecting shifting demographics and rising black political influence.

Rebirth and Diversity: Oakland Today

Beginning in the 1970s and accelerating in the following decades, Oakland began to reinvent itself. The new BART trains helped revive downtown, and city officials launched efforts to draw residents back into the core. For example, Mayor Jerry Brown’s “10K Plan” (1999) aimed to bring 10,000 people into the city center, spurring new housing, shops, and restaurants. By the 1980s and 90s, Oakland’s population rebounded past its mid-century level. The city remained ethnically diverse: immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere have joined long-established black and white communities. Markets now feature foods from around the world, and over 70 languages are spoken in Oakland’s schools.

According to Smithsonian magazine, for decades Oakland has been “the gritty working-class cousin to nearby San Francisco,” prized by many newcomers for its relative affordability, sunnier weather, and rich cultural diversity. This reputation has only grown in recent years as Oakland has become known for its vibrant arts scene, craft breweries, and bustling Jack London Square waterfront. (In fact, Oakland’s Jack London Square is named for the famous author who grew up in the city, and it preserves historic docks and buildings from the 19th century.) Today Oakland continues to grow with tech companies moving in, the Warriors basketball team winning an NBA championship, and new apartment towers rising.

Despite these changes, many Oaklanders emphasize remembering the past. Urban historians and community leaders note that new development often builds over old history. As Oakland librarian Dorothy Lazard has observed, “History is being rewritten very rapidly, but it’s also being forgotten very rapidly”. Advocates point out that beneath modern buildings lie the remnants of Ohlone villages and World War II shipyards. For instance, Ruth Orta and Corrina Gould – Chochenyo Ohlone leaders – have worked to protect the remnants of the West Berkeley Shellmound, one of the last physical links to Oakland’s earliest inhabitants. These efforts highlight a simple truth: Oakland’s rich history – from native villages and oak-covered hills to industrial ports and activist movements – still shapes the city’s identity. Understanding that history helps residents appreciate who Oakland was and who it is becoming.

Conclusion: Oakland’s journey from an ancient Ohlone homeland to a bustling modern city is full of surprising turns. Each layer of the past – native culture, Spanish and Mexican ranchos, Gold Rush growth, wartime industry, civil rights activism – is woven into Oakland’s fabric. The city’s oak-lined streets, historic parks, and community stories are reminders of this legacy. Today’s Oaklanders live among skyscrapers and street art, but the city’s soul is grounded in its history. By exploring where Oakland has been, we gain a deeper appreciation for where it’s headed.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Who were the original inhabitants of Oakland?

For thousands of years the Oakland area was home to the Ohlone (Costanoan) Native American tribes, who lived off the land and built large shellmounds along the Bay.

-

Why is Oakland called “Oakland”?

Oakland was named by early settlers for the abundant oak trees that covered the grassy plains. In 1852 Horace Carpentier and partners formally named the new town Oakland when it was incorporated.

-

When was Oakland founded or incorporated?

Oakland was incorporated as a town on May 4, 1852. It grew out of several smaller settlements (including neighboring Brooklyn) and became a city a few years later.

-

What was Rancho San Antonio?

Rancho San Antonio was a vast 44,800-acre land grant given by the Spanish crown in 1820 to Luis María Peralta. It included much of modern Oakland and neighboring cities. The Peralta family held the rancho under both Spanish and Mexican rule, and later portions were sold to American settlers.

-

How did Oakland get started as a city?

In the early 1850s settlers like Horace Carpentier planned and laid out the streets of Oakland. They built ferries across the bay and attracted commerce. The town grew quickly with the Gold Rush, and when it was incorporated in 1852 it already had a bustling port and railroad connections.

-

What role did Oakland play in the Gold Rush?

During the California Gold Rush (1849 and after), Oakland served as a transit and supply center. Ships and prospectors landed in the East Bay to travel north, and Oakland’s port and ferry system carried goods and people to gold regions. The city’s location and infrastructure made it an important hub in that era.

-

What happened during World War II in Oakland?

World War II transformed Oakland into a shipbuilding and industrial center. Kaiser Shipyards and Moore Dry Dock built warships along the bay. Many Southern African American workers migrated here for these jobs; by 1950 Oakland’s Black population had jumped dramatically compared to 1940. This period reshaped the city’s demographics and economy.

-

When and why was the Black Panther Party founded in Oakland?

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland in 1966 by activists Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. It emerged in response to police brutality and racial inequality in the city’s African-American neighborhoods. The Panthers became one of the most prominent Black Power organizations of the era, establishing community programs and challenging injustice.

-

What is special about Lake Merritt in Oakland’s history?

Lake Merritt is a tidal lagoon in downtown Oakland that was converted into a park and lake by the late 1800s. In 1870 it was set aside as the first official wildlife refuge in the United States (one of the earliest conservation moves). Today it remains a central urban park and lagoon surrounded by city streets.

-

How is Oakland’s history reflected in the city today?

Oakland’s history lives on in many ways. Street and neighborhood names (like Temescal and Rockridge) recall Native and early settler terms. Historic sites – from old tree-lined parks to preserved farms and ships – dot the city. Festivals and museums celebrate multicultural and activist heritage. Even the city’s passionate community spirit and diversity echo the layers of Oakland’s past.

Pingback: From Gold Rush Suds to Hoppy Havens: A Deep Dive into Oakland's Craft Beer History - Oakland Explore